Crazy bastard.

excerpt:

Full article with more history here: http://cycling.ahands.org/bicycling/datewithdeath.html

excerpt:

Date with Death

by Clifford L. Graves, M.D.

September 1965

A tense group of people was gathered on the freeway near the German town of Friedburg on July 19, 1962.

Herr Heinemann had painstakingly measured off the official kilometer. Half a dozen timekeepers of the International Timing Association were fiddling with their electrical equipment. Captain Dalicampt of the French occupation forces deployed his men at strategic points along the cleared Autobahn. Chief Schefold of the federal highway department dispatched a sweeper crew. Adolf Zimber lovingly wiped a bit of invisible dirt off the windshield of his massive Mercedes. Reporters were asking questions, scribbling notes. A photographer was angling for a shot. José Meiffret was about to start his Date with Death.

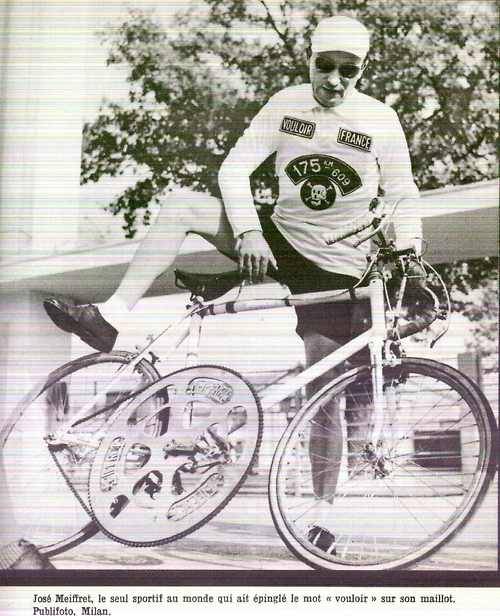

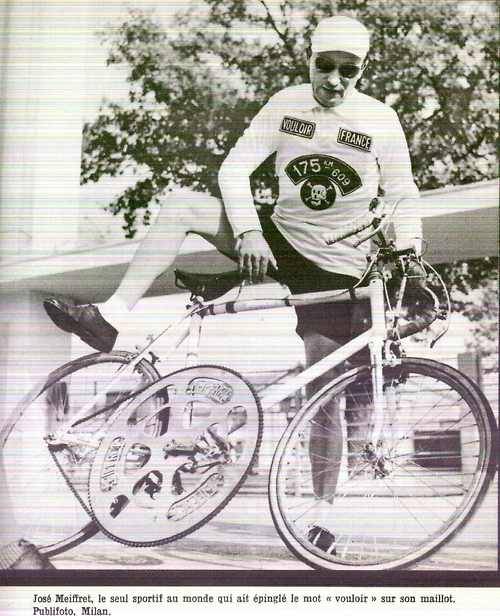

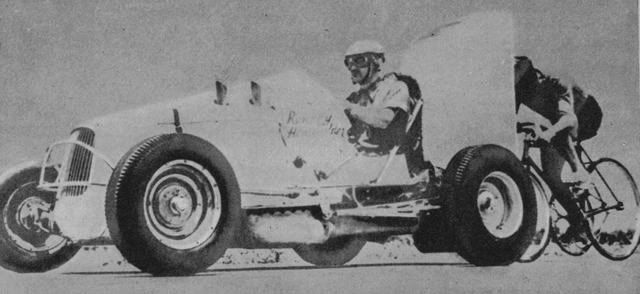

Of all the tense people, Meiffret was the least so. A diminutive Frenchman with wistful eyes and a troubled expression, he was resting beside a strange-looking bicycle. A monstrous chain wheel with 130 teeth connected with a sprocket with 15. The rake on the fork was reversed. Rims were of wood to prevent overheating. The gooseneck was supported with a flying buttress. The well-worn tires were tubulars. The frame was reinforced at all the critical points. Weighting forty-five pounds, this machine was obviously constructed to withstand incredible punishment.

On this day, at this place, on this bicycle, José Meiffret was aiming to reach the fantastic speed of 124 miles an hour. Everything was now in readiness. Meiffret adjusted his helmet, mounted the bike, and tighten the toe straps. Getting under way with a gear of 225 inches was something else again. A motorcycle came alongside and started pushing him. At 20 miles an hour, Meiffret was struggling to gain control. His legs were barely moving. At 40 miles, he was beginning to hit his stride. At 50 miles, the Mercedes with its curious rear end was just behind. With a wave of his hand, Meiffret dismissed his motorcycle and connected neatly with the windscreen of the Mercedes. His timing was perfect. He had overcome his first great hazard.

Swiftly, the bizarre combination of man and machine gathered speed. Meiffret's job on penalty of death was to stay glued to his windscreen. The screen had a roller, but if he should touch it at 100 miles an hour, he would be clipped. On the other hand, if he should fall behind as little as 18 inches, the turbulence would make mincemeat of him. If the car should jerk or lurch or hit a bump, he would be in immediate mortal danger. An engineer had warned him that at these speeds, the centrifugal force might cause his flimsy wheels to collapse. Undismayed b the prospect, Meiffret bent down to his task.

He was now moving at 80 miles. News of the heroic attempt had spread, and the road ahead was lined with spectators. Everybody was expecting something dreadful to happen. Herr Thiergarten in the car showed Meiffret how fast he was going by prearranged signals. Meiffret in turn could speak to the driver through a microphone. "Allez, allez," he shouted, knowing that he had only nine miles to accelerate and decelerate. The speedometer showed 90. What if he should hit a pebble, an oil slick, a gust of wind? Ahead was bridge and clump of woods. Crosscurrents were inevitable.

"In his pocket, Meiffret carried a note:

"In case of fatal accident, I beg of the spectators not to feel sorry for me. I am a poor man, an orphan since the age of eleven, and I have suffered much. Death holds no terror for me. This record attempt is my way of expressing myself. If the doctors can do no more for me, please bury me by the side of the road where I have fallen."

Who was this man Meiffret who could ride a bicycle at such passionate speeds and still look at himself dispassionately?

[personal history removed, read at link]

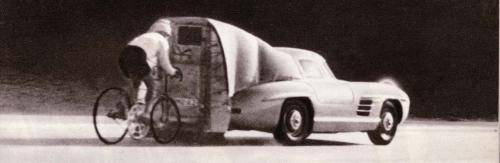

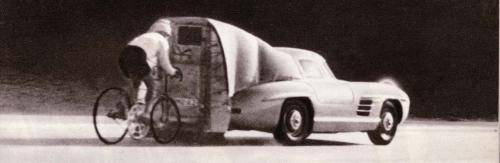

The Mercedes performed flawlessly. People could not believe their eyes. What they saw was the car in full flight with and arched figure immediately behind, legs whirling, jersey fluttering, wheels quivering. "Allez, allez," gasped Meiffret into the mike. In the car, the speedometer crept past 100 mph, then 110 and 120. Anguished, Zimber looked into his rear-view mirror. How could Meiffret keep himself positioned? It was fantastic.

At the flat, the speed had increased to 127. Faster than an express train, faster than a plummeting skier, faster than a free fall in space. Meiffret's legs were spinning at 3.1 revolutions per second, and each second carried him 190 feet! He was no longer a man on a bike. He was the flying Frenchman, the superman of the bicycle, the magician of the pedals, the eagle of the road, the poet of motion. He knew that he must live in the rarefied atmosphere for eighteen seconds. When he passed the second flag, the chronometers registered 17.580 seconds, equivalent to 127.342 miles an hour.

Meiffret had survived his date with death.

by Clifford L. Graves, M.D.

September 1965

A tense group of people was gathered on the freeway near the German town of Friedburg on July 19, 1962.

Herr Heinemann had painstakingly measured off the official kilometer. Half a dozen timekeepers of the International Timing Association were fiddling with their electrical equipment. Captain Dalicampt of the French occupation forces deployed his men at strategic points along the cleared Autobahn. Chief Schefold of the federal highway department dispatched a sweeper crew. Adolf Zimber lovingly wiped a bit of invisible dirt off the windshield of his massive Mercedes. Reporters were asking questions, scribbling notes. A photographer was angling for a shot. José Meiffret was about to start his Date with Death.

Of all the tense people, Meiffret was the least so. A diminutive Frenchman with wistful eyes and a troubled expression, he was resting beside a strange-looking bicycle. A monstrous chain wheel with 130 teeth connected with a sprocket with 15. The rake on the fork was reversed. Rims were of wood to prevent overheating. The gooseneck was supported with a flying buttress. The well-worn tires were tubulars. The frame was reinforced at all the critical points. Weighting forty-five pounds, this machine was obviously constructed to withstand incredible punishment.

On this day, at this place, on this bicycle, José Meiffret was aiming to reach the fantastic speed of 124 miles an hour. Everything was now in readiness. Meiffret adjusted his helmet, mounted the bike, and tighten the toe straps. Getting under way with a gear of 225 inches was something else again. A motorcycle came alongside and started pushing him. At 20 miles an hour, Meiffret was struggling to gain control. His legs were barely moving. At 40 miles, he was beginning to hit his stride. At 50 miles, the Mercedes with its curious rear end was just behind. With a wave of his hand, Meiffret dismissed his motorcycle and connected neatly with the windscreen of the Mercedes. His timing was perfect. He had overcome his first great hazard.

Swiftly, the bizarre combination of man and machine gathered speed. Meiffret's job on penalty of death was to stay glued to his windscreen. The screen had a roller, but if he should touch it at 100 miles an hour, he would be clipped. On the other hand, if he should fall behind as little as 18 inches, the turbulence would make mincemeat of him. If the car should jerk or lurch or hit a bump, he would be in immediate mortal danger. An engineer had warned him that at these speeds, the centrifugal force might cause his flimsy wheels to collapse. Undismayed b the prospect, Meiffret bent down to his task.

He was now moving at 80 miles. News of the heroic attempt had spread, and the road ahead was lined with spectators. Everybody was expecting something dreadful to happen. Herr Thiergarten in the car showed Meiffret how fast he was going by prearranged signals. Meiffret in turn could speak to the driver through a microphone. "Allez, allez," he shouted, knowing that he had only nine miles to accelerate and decelerate. The speedometer showed 90. What if he should hit a pebble, an oil slick, a gust of wind? Ahead was bridge and clump of woods. Crosscurrents were inevitable.

"In his pocket, Meiffret carried a note:

"In case of fatal accident, I beg of the spectators not to feel sorry for me. I am a poor man, an orphan since the age of eleven, and I have suffered much. Death holds no terror for me. This record attempt is my way of expressing myself. If the doctors can do no more for me, please bury me by the side of the road where I have fallen."

Who was this man Meiffret who could ride a bicycle at such passionate speeds and still look at himself dispassionately?

[personal history removed, read at link]

The Mercedes performed flawlessly. People could not believe their eyes. What they saw was the car in full flight with and arched figure immediately behind, legs whirling, jersey fluttering, wheels quivering. "Allez, allez," gasped Meiffret into the mike. In the car, the speedometer crept past 100 mph, then 110 and 120. Anguished, Zimber looked into his rear-view mirror. How could Meiffret keep himself positioned? It was fantastic.

At the flat, the speed had increased to 127. Faster than an express train, faster than a plummeting skier, faster than a free fall in space. Meiffret's legs were spinning at 3.1 revolutions per second, and each second carried him 190 feet! He was no longer a man on a bike. He was the flying Frenchman, the superman of the bicycle, the magician of the pedals, the eagle of the road, the poet of motion. He knew that he must live in the rarefied atmosphere for eighteen seconds. When he passed the second flag, the chronometers registered 17.580 seconds, equivalent to 127.342 miles an hour.

Meiffret had survived his date with death.

Comment