LIEUTENANT COLONEL JIMMY DOOLITTLE at the controls of a B-25 Mitchell medium bomber, zoomed low over northern Tokyo at midday on Saturday, April 18, 1942. He could see the high-rises crowding the Japanese capital’s business district as well as the imperial palace and even the muddy moat encircling Emperor Hirohito’s home.

“Approaching target,” the airman told his bombardier.

Doolittle pulled back on the yoke, climbing to 1,200 feet. The B-25’s bomb bay doors yawned.

“All ready, Colonel,” the bombardier said.

Amid antiaircraft fire from startled gunners on the ground, Doolittle leveled off over northern Tokyo. At 1:15 p.m. the red light on his instrument panel blinked as his first bomb plummeted. The light flashed again.

Then again.

And again.

Four bombs—each packed with 128 four-pound incendiary bomblets—tumbled onto Tokyo as Doolittle dove to rooftop level and turned south, back toward the Pacific. The veteran airman had accomplished what four months earlier had seemed impossible. The United States had bombed the Japanese homeland, a feat of arms and daring aviation that would stiffen the resolve of a demoralized America.

For more than seven decades Americans have celebrated the Doolittle Raid largely for reasons that have little to do with the mission’s tactical impact. A handful of bombers, each carrying two tons of ordnance, after all, could hardly dent a war machine that dominated nearly a tenth of the globe. Rather, the focus has been on the ingenuity, grit, and heroism required to execute what amounted to a virtual suicide mission, which Vice Admiral William Halsey Jr. hailed in a personal letter to Doolittle. “I do not know of any more gallant deed in history than that performed by your squadron,” wrote Halsey, who commanded the task force that transported Doolittle and his men to Japan. “You have made history.”

But the raid did have a significant impact, some of those outcomes positive, some very dark. The American bomber squadron inflicted widespread damage in the target areas but also caused civilian deaths that included children at school. In retaliatory campaigns that went on for months, Japanese military units killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese. And in the years following the Japanese surrender, American occupation authorities sheltered a general suspected of war crimes against some of the aviators. All these facts have been illuminated only recently through declassified records and other previously untapped archival sources.

The new information in no way undermines the bravery of the first Americans to fly against Japan’s homeland. Rather it shows that after more than 70 years, one of the war’s best known and most iconic stories still has the power to reveal more about its intricacies and effectiveness.

EVEN AS CREWS were recovering American dead from Pearl Harbor’s oily waters, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was demanding that his senior military leaders take the fight to Tokyo. As Army Air Forces chief Lieutenant General Henry Arnold later wrote, “The president was insistent that we find ways and means of carrying home to Japan proper, in the form of a bombing raid, the real meaning of war.”

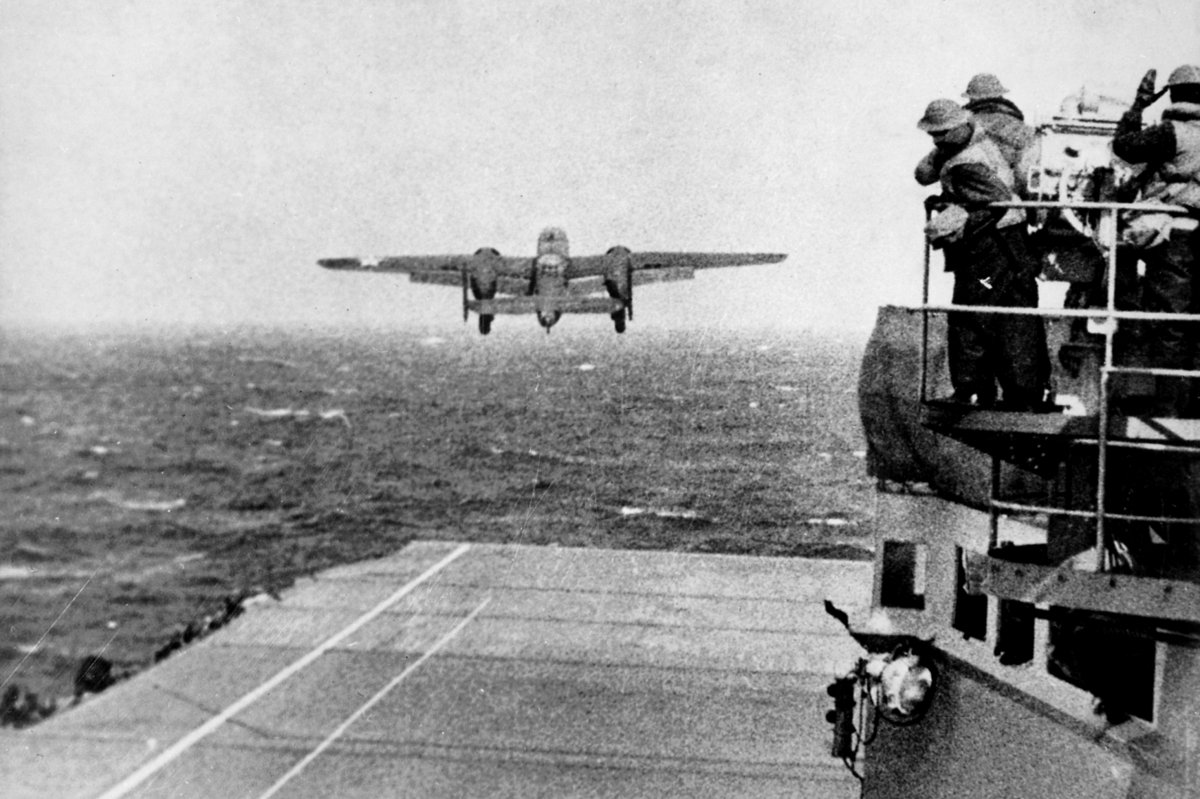

Thus the concept of a surprise attack on the Japanese capital was born. Within weeks, a plan emerged. An aircraft carrier protected by a 15-ship task force—including a second carrier, four cruisers, eight destroyers, and two oilers—would steam into striking distance of Tokyo. Taking off from the carrier—something never before attempted—16 B-25 medium bombers would assault Tokyo and the industrial cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, Kanagawa, Kobe, and Osaka. After spreading destruction across more than 200 miles, the airmen would fly to regions of China controlled by the Nationalists. Navy planners had the perfect vessel in mind—the USS Hornet, America’s newest flattop. The Tokyo raid would be the $32 million carrier’s first combat mission.

To oversee the Army Air Forces’ role, Arnold tapped his staff troubleshooter, Doolittle. The 45-year-old had chafed his way through World War I, forced because of his excellent flying skills to train others. “My students were going overseas and becoming heroes,” he later griped. “My job was to make more heroes.” What Doolittle lacked in combat experience, the airman with an ear-to-ear to grin—and MIT doctorate—more than made up for in intelligence and daring, character traits that would prove vital to the Tokyo raid’s success.

But where to bomb in Tokyo, and what? One Japanese in 10 lived there. The population was nearly seven million, making Japan’s capital the world’s third largest city after London and New York. In some areas population density exceeded 100,000 per square mile, with factories, homes, and stores jumbled together. Commercial workshops often doubled as private residences, even in areas classified as industrial.

As they studied maps, the colonel drilled his 79 volunteer pilots, navigators, and bombardiers on the need to hit only legitimate military targets. “Crews were repeatedly briefed to avoid any action that could possibly give the Japanese any ground to say that we had bombed or strafed indiscriminately,” he said. “Specifically, they were told to stay away from hospitals, schools, museums, and anything else that was not a military target.” But there was no guarantee. “It is quite impossible to bomb a military objective that has civilian residences near it without danger of harming the civilian residences as well,” Doolittle said. “That is a hazard of war.”

“Approaching target,” the airman told his bombardier.

Doolittle pulled back on the yoke, climbing to 1,200 feet. The B-25’s bomb bay doors yawned.

“All ready, Colonel,” the bombardier said.

Amid antiaircraft fire from startled gunners on the ground, Doolittle leveled off over northern Tokyo. At 1:15 p.m. the red light on his instrument panel blinked as his first bomb plummeted. The light flashed again.

Then again.

And again.

Four bombs—each packed with 128 four-pound incendiary bomblets—tumbled onto Tokyo as Doolittle dove to rooftop level and turned south, back toward the Pacific. The veteran airman had accomplished what four months earlier had seemed impossible. The United States had bombed the Japanese homeland, a feat of arms and daring aviation that would stiffen the resolve of a demoralized America.

For more than seven decades Americans have celebrated the Doolittle Raid largely for reasons that have little to do with the mission’s tactical impact. A handful of bombers, each carrying two tons of ordnance, after all, could hardly dent a war machine that dominated nearly a tenth of the globe. Rather, the focus has been on the ingenuity, grit, and heroism required to execute what amounted to a virtual suicide mission, which Vice Admiral William Halsey Jr. hailed in a personal letter to Doolittle. “I do not know of any more gallant deed in history than that performed by your squadron,” wrote Halsey, who commanded the task force that transported Doolittle and his men to Japan. “You have made history.”

But the raid did have a significant impact, some of those outcomes positive, some very dark. The American bomber squadron inflicted widespread damage in the target areas but also caused civilian deaths that included children at school. In retaliatory campaigns that went on for months, Japanese military units killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese. And in the years following the Japanese surrender, American occupation authorities sheltered a general suspected of war crimes against some of the aviators. All these facts have been illuminated only recently through declassified records and other previously untapped archival sources.

The new information in no way undermines the bravery of the first Americans to fly against Japan’s homeland. Rather it shows that after more than 70 years, one of the war’s best known and most iconic stories still has the power to reveal more about its intricacies and effectiveness.

EVEN AS CREWS were recovering American dead from Pearl Harbor’s oily waters, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was demanding that his senior military leaders take the fight to Tokyo. As Army Air Forces chief Lieutenant General Henry Arnold later wrote, “The president was insistent that we find ways and means of carrying home to Japan proper, in the form of a bombing raid, the real meaning of war.”

Thus the concept of a surprise attack on the Japanese capital was born. Within weeks, a plan emerged. An aircraft carrier protected by a 15-ship task force—including a second carrier, four cruisers, eight destroyers, and two oilers—would steam into striking distance of Tokyo. Taking off from the carrier—something never before attempted—16 B-25 medium bombers would assault Tokyo and the industrial cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, Kanagawa, Kobe, and Osaka. After spreading destruction across more than 200 miles, the airmen would fly to regions of China controlled by the Nationalists. Navy planners had the perfect vessel in mind—the USS Hornet, America’s newest flattop. The Tokyo raid would be the $32 million carrier’s first combat mission.

To oversee the Army Air Forces’ role, Arnold tapped his staff troubleshooter, Doolittle. The 45-year-old had chafed his way through World War I, forced because of his excellent flying skills to train others. “My students were going overseas and becoming heroes,” he later griped. “My job was to make more heroes.” What Doolittle lacked in combat experience, the airman with an ear-to-ear to grin—and MIT doctorate—more than made up for in intelligence and daring, character traits that would prove vital to the Tokyo raid’s success.

But where to bomb in Tokyo, and what? One Japanese in 10 lived there. The population was nearly seven million, making Japan’s capital the world’s third largest city after London and New York. In some areas population density exceeded 100,000 per square mile, with factories, homes, and stores jumbled together. Commercial workshops often doubled as private residences, even in areas classified as industrial.

As they studied maps, the colonel drilled his 79 volunteer pilots, navigators, and bombardiers on the need to hit only legitimate military targets. “Crews were repeatedly briefed to avoid any action that could possibly give the Japanese any ground to say that we had bombed or strafed indiscriminately,” he said. “Specifically, they were told to stay away from hospitals, schools, museums, and anything else that was not a military target.” But there was no guarantee. “It is quite impossible to bomb a military objective that has civilian residences near it without danger of harming the civilian residences as well,” Doolittle said. “That is a hazard of war.”

Comment