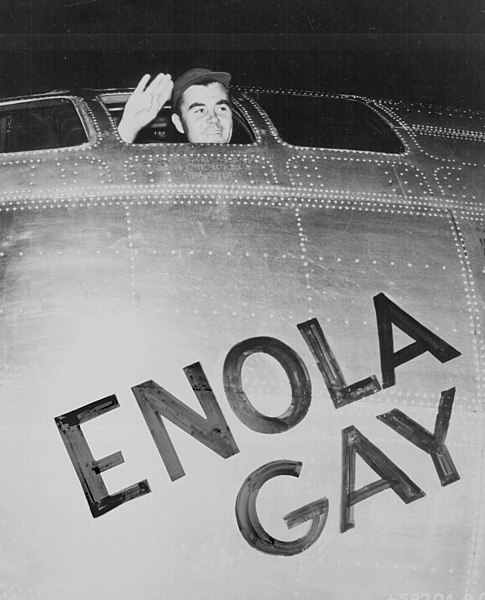

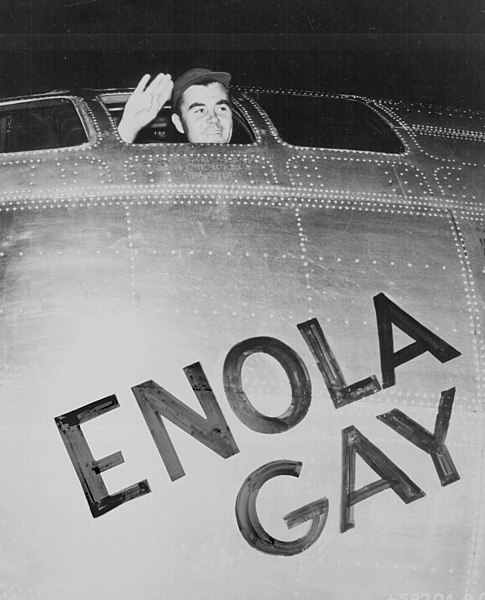

Col. Paul Tibbets and his crew changed the world.

16 hours after the drop Truman had this to say:

So much fuck yeah in that statement.

But DAMN, we had to wreck some shit to get to that point.

The rest can be read here:

16 hours after the drop Truman had this to say:

"Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima. It is an atomic bomb. We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth."

So much fuck yeah in that statement.

But DAMN, we had to wreck some shit to get to that point.

Little Boy was ready for delivery by July 31. On August 2, Hiroshima was specified as the primary target, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternates. The raid was set for August 6.

While plans for the invasion of Japan were going ahead, preparations were also being made for the use of the atomic bomb. Target recommendations were made by the Target Committee. Among its primary concerns was showing off the bomb's power to the maximum effect. By the end of May 1945, the Committee selected, in order of priority, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kokura and Niigata. The Army Air Forces were ordered not to firebomb these cities.

Hiroshima was chosen as the primary target since it had remained largely untouched by bombing raids, and the bomb's effects could be clearly measured. While President Truman had hoped for a purely military target, some advisers believed that bombing an urban area might break the fighting will of the Japanese people. Hiroshima was a major port and a military headquarters, and therefore a strategic target. Also, visual bombing, rather than radar, would be used so that photographs of the damage could be taken. Since Hiroshima had not been seriously harmed by bombing raids, these photographs could present a fairly clear picture of the bomb's damage.

When the Japanese military ignored the Potsdam Declaration's threat of "prompt and utter destruction," Groves drafted the orders to use the bomb and sent them to General Carl Spaatz, commander of air forces in the Pacific. Upon approval by Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, Secretary of War Stimson and President Truman, the order to drop Little Boy on Hiroshima had officially been given.

Before Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima, Leo Szilard at Met Lab in Chicago tried to stop its use. Ironically, Szilard had led atomic bomb research in 1939, but since the threat of a German bomb was over, he started a petition to President Truman against bombing Japan. With 88 signatures on the petition, Szilard circulated copies in Chicago and Oak Ridge, only to have the petition quashed at Los Alamos by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

When General Leslie Groves learned of the petition, he polled the Met Lab scientists and learned that only 15 percent wanted the bomb used "in the most effective military manner." While 46 percent voted for "military demonstration in Japan to be followed by a new opportunity for surrender before full use of the weapon is employed," somehow the figures were manipulated to suggest that 87 percent of the Met Lab scientists favored some sort of military use. Ultimately, Groves sat on Szilard's petition and the poll until August 1, and then had them filed away. President Truman never saw them.

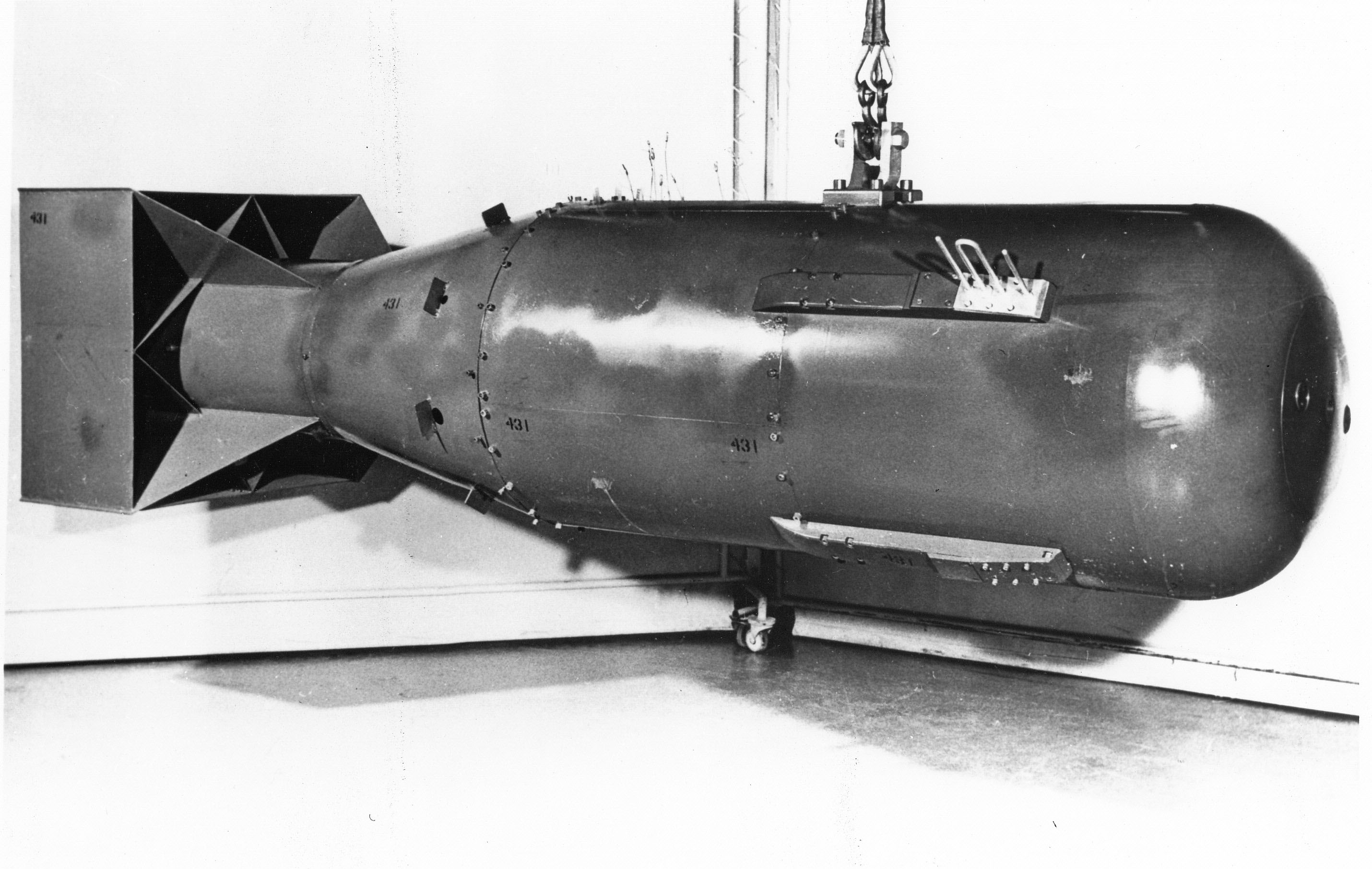

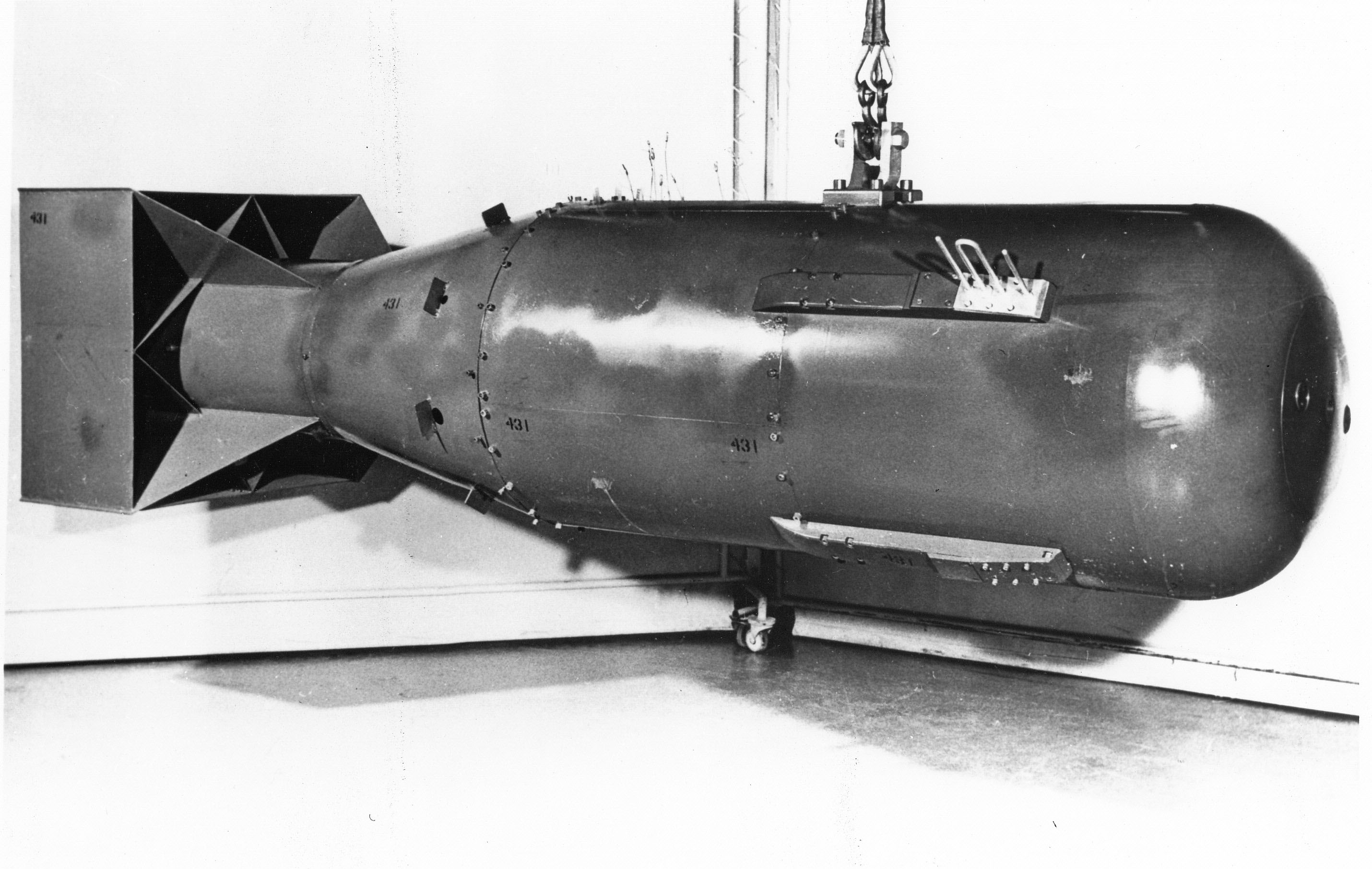

At approximately 2:00 a.m. on August 6, 1945, a modified American B-29 Superfortress bomber named the Enola Gay left the island of Tinian for Hiroshima, Japan. This mission was piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, commanding officer of the 509th Composite Group, who named the bomber after his mother. The four-engine plane, followed by two observation planes carrying cameras and scientific instruments, was one of seven making the trip to Hiroshima, but only the Enola Gay was carrying a bomb—a bomb that was expected to knock out almost everything within a 3-mile (5-kilometer) area. Measuring over 10 feet (3 meters) long and almost 30 inches (75 centimeters) across, it weighed close to 5 tons (4.5 tonnes) and had the explosive force of 20,000 tons (18,000 tonnes) of TNT.

The Enola Gay weaponeer, Navy Capt. Deak Parsons, was concerned about taking off with Little Boy fully assembled and live. Some heavily loaded B-29s had crashed on takeoff from Tinian. If that happened to the Enola Gay, the bomb might explode and wipe out half the island. Thus, Parsons, assisted by Lt. Morris Jeppson, finished the assembly and armed the bomb in the bomb bay after takeoff.

After 6:00, the bomb was fully armed on board the Enola Gay. Tibbets announced to the crew that the plane was carrying the world's first atomic bomb. By 7:00, the Japanese radar net detected aircraft heading toward Japan, and the alert was broadcast throughout the Hiroshima area. Soon afterward, a weather plane circled over the city, but there was no sign of bombers. The people began their daily work and thought the danger had passed.

At 7:25, the Enola Gay was cruising over Hiroshima at 26,000 feet. By 8:00, Japanese radar again detected B-29s heading toward the city. Radio stations broadcast another warning for people to take shelter, but many ignored it. At 8:09, the crew of the Enola Gay could see the city appear below and received a message indicating that the weather was good over Hiroshima.

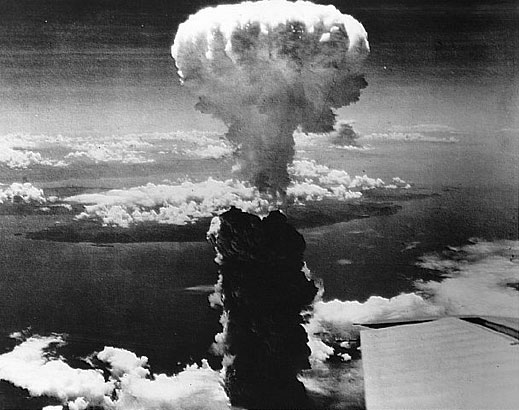

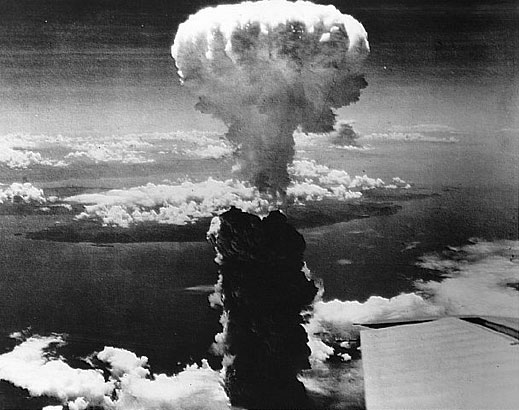

A T-shaped bridge at the junction of the Honkawa and Motoyasu rivers near downtown Hiroshima was the target. At 8:15 a.m., Little Boy exploded, instantly killing 80,000 to 140,000 people and seriously injuring 100,000 more. The bomb exploded some 1,900 feet above the center of the city, over Shima Surgical Hospital, some 70 yards southeast of the Industrial Promotional Hall (now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome). Crewmembers of the Enola Gay saw a column of smoke rising fast and intense fires springing up. The burst temperature was estimated to reach over a million degrees Celsius, which ignited the surrounding air, forming a fireball some 840 feet in diameter. Eyewitnesses more than 5 miles away said its brightness exceeded the sun tenfold.

In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima's buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.

To the crew of the Enola Gay, Hiroshima had disappeared under a thick, churning foam of flames and smoke. The co-pilot, Captain Robert Lewis, commented, "My God, what have we done?"

While plans for the invasion of Japan were going ahead, preparations were also being made for the use of the atomic bomb. Target recommendations were made by the Target Committee. Among its primary concerns was showing off the bomb's power to the maximum effect. By the end of May 1945, the Committee selected, in order of priority, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kokura and Niigata. The Army Air Forces were ordered not to firebomb these cities.

Hiroshima was chosen as the primary target since it had remained largely untouched by bombing raids, and the bomb's effects could be clearly measured. While President Truman had hoped for a purely military target, some advisers believed that bombing an urban area might break the fighting will of the Japanese people. Hiroshima was a major port and a military headquarters, and therefore a strategic target. Also, visual bombing, rather than radar, would be used so that photographs of the damage could be taken. Since Hiroshima had not been seriously harmed by bombing raids, these photographs could present a fairly clear picture of the bomb's damage.

When the Japanese military ignored the Potsdam Declaration's threat of "prompt and utter destruction," Groves drafted the orders to use the bomb and sent them to General Carl Spaatz, commander of air forces in the Pacific. Upon approval by Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, Secretary of War Stimson and President Truman, the order to drop Little Boy on Hiroshima had officially been given.

Before Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima, Leo Szilard at Met Lab in Chicago tried to stop its use. Ironically, Szilard had led atomic bomb research in 1939, but since the threat of a German bomb was over, he started a petition to President Truman against bombing Japan. With 88 signatures on the petition, Szilard circulated copies in Chicago and Oak Ridge, only to have the petition quashed at Los Alamos by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

When General Leslie Groves learned of the petition, he polled the Met Lab scientists and learned that only 15 percent wanted the bomb used "in the most effective military manner." While 46 percent voted for "military demonstration in Japan to be followed by a new opportunity for surrender before full use of the weapon is employed," somehow the figures were manipulated to suggest that 87 percent of the Met Lab scientists favored some sort of military use. Ultimately, Groves sat on Szilard's petition and the poll until August 1, and then had them filed away. President Truman never saw them.

At approximately 2:00 a.m. on August 6, 1945, a modified American B-29 Superfortress bomber named the Enola Gay left the island of Tinian for Hiroshima, Japan. This mission was piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, commanding officer of the 509th Composite Group, who named the bomber after his mother. The four-engine plane, followed by two observation planes carrying cameras and scientific instruments, was one of seven making the trip to Hiroshima, but only the Enola Gay was carrying a bomb—a bomb that was expected to knock out almost everything within a 3-mile (5-kilometer) area. Measuring over 10 feet (3 meters) long and almost 30 inches (75 centimeters) across, it weighed close to 5 tons (4.5 tonnes) and had the explosive force of 20,000 tons (18,000 tonnes) of TNT.

The Enola Gay weaponeer, Navy Capt. Deak Parsons, was concerned about taking off with Little Boy fully assembled and live. Some heavily loaded B-29s had crashed on takeoff from Tinian. If that happened to the Enola Gay, the bomb might explode and wipe out half the island. Thus, Parsons, assisted by Lt. Morris Jeppson, finished the assembly and armed the bomb in the bomb bay after takeoff.

After 6:00, the bomb was fully armed on board the Enola Gay. Tibbets announced to the crew that the plane was carrying the world's first atomic bomb. By 7:00, the Japanese radar net detected aircraft heading toward Japan, and the alert was broadcast throughout the Hiroshima area. Soon afterward, a weather plane circled over the city, but there was no sign of bombers. The people began their daily work and thought the danger had passed.

At 7:25, the Enola Gay was cruising over Hiroshima at 26,000 feet. By 8:00, Japanese radar again detected B-29s heading toward the city. Radio stations broadcast another warning for people to take shelter, but many ignored it. At 8:09, the crew of the Enola Gay could see the city appear below and received a message indicating that the weather was good over Hiroshima.

A T-shaped bridge at the junction of the Honkawa and Motoyasu rivers near downtown Hiroshima was the target. At 8:15 a.m., Little Boy exploded, instantly killing 80,000 to 140,000 people and seriously injuring 100,000 more. The bomb exploded some 1,900 feet above the center of the city, over Shima Surgical Hospital, some 70 yards southeast of the Industrial Promotional Hall (now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome). Crewmembers of the Enola Gay saw a column of smoke rising fast and intense fires springing up. The burst temperature was estimated to reach over a million degrees Celsius, which ignited the surrounding air, forming a fireball some 840 feet in diameter. Eyewitnesses more than 5 miles away said its brightness exceeded the sun tenfold.

In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima's buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.

To the crew of the Enola Gay, Hiroshima had disappeared under a thick, churning foam of flames and smoke. The co-pilot, Captain Robert Lewis, commented, "My God, what have we done?"

The rest can be read here:

Comment