The story of Carl McCunn.

What a shitty way to go. Not quite as retarded as Christopher McCandless (aka. Alexander Supertramp), but still fucking stupid. I love the outdoors as much as anyone, and I wont even do day hikes in the mountains without telling people where we're going, when we're returning, etc.

He actually wrote in his diary:

"I think I should have used more foresight about arranging my departure."

(BTW, this article was written in 1982... his ordeal happened in the summer/fall of 1981)

What a shitty way to go. Not quite as retarded as Christopher McCandless (aka. Alexander Supertramp), but still fucking stupid. I love the outdoors as much as anyone, and I wont even do day hikes in the mountains without telling people where we're going, when we're returning, etc.

He actually wrote in his diary:

"I think I should have used more foresight about arranging my departure."

(BTW, this article was written in 1982... his ordeal happened in the summer/fall of 1981)

Left in Wilds, Man Penned Dying Record

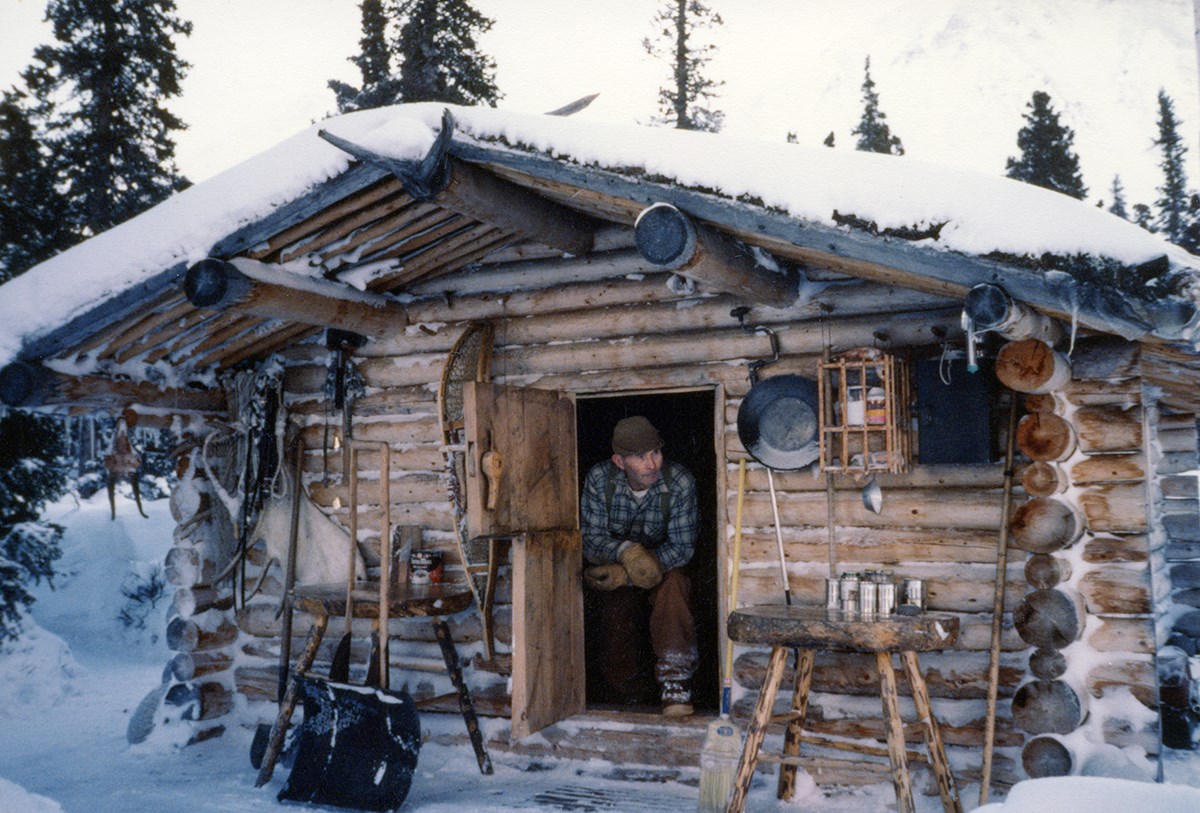

FAIRBANKS, Alaska, Dec. 18— Tales of death and despair in the frozen north are not new in Alaskan folklore, but seldom have men recorded their own fatal adventure as graphically as Carl McCunn, a photographer of wildlife.

When a state trooper cut open the tent and found Mr. McCunn's wasted body last Feb. 2, he also found a diary the starving man had kept until he ended his suffering with a rifle bullet.

''They say it doesn't hurt,'' the 35-year-old Mr. McCunn wrote before he pulled the trigger. He died in a wilderness camp near a nameless lake in a nameless valley 225 miles northeast of Fairbanks. He had gone there to photograph the tundra. But he had not been specific about plans to be flown out, and so he was stranded and ran out of food.

His diary, 100 pages of looseleaf paper, began in tidy, block letters recording the wonders of an emerging summer. It ended, eight and a half months later, in the scrawl of an abandoned soul crippled by frostbite, scavenging the half-eaten prey of foxes.

Tale From Coroner's Office

The diary wound up in the coroner's office here, where, at an inquest, the plight of Mr. McCunn unfolded. On the last page, he wrote: ''Am burning the last of my emergency Coleman light and just fed the fire the last of my split wood. When the ashes cool, I'll be cooling along with them.''

Mr. McCunn had been flown into the valley in March 1981 as winter was ending. He knew the area. In 1976, he had spent five months alone in the desolate Brooks Range.

This time, with about 500 rolls of film, photography equipment, firearms and 1,400 pounds of provisions, he had planned to stay through mid-August.

His father, Donovan McCunn of San Antonio, Tex., described his son as 6 feet, 2 inches tall, weighing 240 pounds, with curly, reddish blond hair and an outgoing personality. He was born in West Germany to an Army family.

Four Years in the Navy

After high school, he went to college for a semester before joining the Navy for a four-year tour. Then he worked on a ferry between Washington State and Alaska and did odd jobs after making his home in Alaska, probably in 1970.

At the coroner's inquest, testimony from friends and notes from Mr. McCunn's diary suggested that he had failed to make specific arrangements to be picked up. The coroner's jury ruled his death a suicide.

In early diary entries, he wrote of the return of the animals to their summer grounds and commented, ''Humans are so out of their 'modern-day' element in a place like this.''

By early August, with his supplies dwindling, his concern grew. ''I think I should have used more foresight about arranging my departure,'' he wrote. ''I'll soon find out.''

By mid-August his diary entries were not dated; he spent much of his time searching for food, shooting some ducks and muskrats and drying the meat of a caribou that died in the lake. His anxiety grew.

He wrote: ''Come on, please. Don't leave me hangin' and frettin' like this. I didn't come out here for that.'' Meanwhile, concerned friends asked the Alaska State Troopers to check on Mr. McCunn. Trooper David Hamilton flew over Mr. McCunn's camp. He testified that he had seen Mr. McCunn waving a red bag. He said he circled, and Mr. McCunn ''waved in a casual manner and watched us fly by.''

''On the third pass he turned and walked back toward the tent, slowly, casually,'' Mr. Hamilton said. ''We surmised there was no immediate danger or need for emergency aid.''

Realized He Gave Wrong Signal

In his diary, Mr. McCunn tells of being elated on sighting the plane, then realizing that he had given the wrong signal to the pilot.

''I recall raising my right hand, shoulder high and shaking my fist on the plane's second pass. It was a little cheer - like when your team scored a touchdown or something.

''Turns out that's the signal for 'ALL O.K. DO NOT WAIT!' Man, I can't believe it!'' Snow came and the lake froze over. He saw his first wolf, ''like a giant husky,'' tried to shoot it with his .22 and heard it yelp. But it crashed away into the underbrush. ''Bad shot and bad show of patience,'' he wrote.

By October, he was competing with wolves and foxes for the rabbits he snared. From the diary: ''It's been a terrible day for me and I won't go into it. Hands getting more frostbitten every day. Have only one meal of beans left. Honestly, I'm scared for my life. But I won't give up.''

In November, Mr. McCunn ran out of food. He considered trying to reach Fort Yukon on foot, 75 miles away. He wrote a letter to his father, telling him how to develop his film. He caught a squirrel, ''but that's only a tease even when you chew up and swallow all the bones too.''

Around Thanksgiving, he began having dizzy spells. ''I feel miserable,'' he wrote. ''Have had the chills upon awakening for the past three days. I can't take much more of this. Can't stop thinking about using the bullet.''

He used the last of his fuel, fed the fire a final time and wrote: ''Dear God in Heaven, please forgive me my weakness and my sins. Please look over my family.'' He added a separate note asking that his personal items be returned to his father, and he said that the person who found him should keep his rifle and shotgun. He signed his name and attached his Alaska driver's license. ''The I.D. is me, natch,'' he said in the diary's last entry.

FAIRBANKS, Alaska, Dec. 18— Tales of death and despair in the frozen north are not new in Alaskan folklore, but seldom have men recorded their own fatal adventure as graphically as Carl McCunn, a photographer of wildlife.

When a state trooper cut open the tent and found Mr. McCunn's wasted body last Feb. 2, he also found a diary the starving man had kept until he ended his suffering with a rifle bullet.

''They say it doesn't hurt,'' the 35-year-old Mr. McCunn wrote before he pulled the trigger. He died in a wilderness camp near a nameless lake in a nameless valley 225 miles northeast of Fairbanks. He had gone there to photograph the tundra. But he had not been specific about plans to be flown out, and so he was stranded and ran out of food.

His diary, 100 pages of looseleaf paper, began in tidy, block letters recording the wonders of an emerging summer. It ended, eight and a half months later, in the scrawl of an abandoned soul crippled by frostbite, scavenging the half-eaten prey of foxes.

Tale From Coroner's Office

The diary wound up in the coroner's office here, where, at an inquest, the plight of Mr. McCunn unfolded. On the last page, he wrote: ''Am burning the last of my emergency Coleman light and just fed the fire the last of my split wood. When the ashes cool, I'll be cooling along with them.''

Mr. McCunn had been flown into the valley in March 1981 as winter was ending. He knew the area. In 1976, he had spent five months alone in the desolate Brooks Range.

This time, with about 500 rolls of film, photography equipment, firearms and 1,400 pounds of provisions, he had planned to stay through mid-August.

His father, Donovan McCunn of San Antonio, Tex., described his son as 6 feet, 2 inches tall, weighing 240 pounds, with curly, reddish blond hair and an outgoing personality. He was born in West Germany to an Army family.

Four Years in the Navy

After high school, he went to college for a semester before joining the Navy for a four-year tour. Then he worked on a ferry between Washington State and Alaska and did odd jobs after making his home in Alaska, probably in 1970.

At the coroner's inquest, testimony from friends and notes from Mr. McCunn's diary suggested that he had failed to make specific arrangements to be picked up. The coroner's jury ruled his death a suicide.

In early diary entries, he wrote of the return of the animals to their summer grounds and commented, ''Humans are so out of their 'modern-day' element in a place like this.''

By early August, with his supplies dwindling, his concern grew. ''I think I should have used more foresight about arranging my departure,'' he wrote. ''I'll soon find out.''

By mid-August his diary entries were not dated; he spent much of his time searching for food, shooting some ducks and muskrats and drying the meat of a caribou that died in the lake. His anxiety grew.

He wrote: ''Come on, please. Don't leave me hangin' and frettin' like this. I didn't come out here for that.'' Meanwhile, concerned friends asked the Alaska State Troopers to check on Mr. McCunn. Trooper David Hamilton flew over Mr. McCunn's camp. He testified that he had seen Mr. McCunn waving a red bag. He said he circled, and Mr. McCunn ''waved in a casual manner and watched us fly by.''

''On the third pass he turned and walked back toward the tent, slowly, casually,'' Mr. Hamilton said. ''We surmised there was no immediate danger or need for emergency aid.''

Realized He Gave Wrong Signal

In his diary, Mr. McCunn tells of being elated on sighting the plane, then realizing that he had given the wrong signal to the pilot.

''I recall raising my right hand, shoulder high and shaking my fist on the plane's second pass. It was a little cheer - like when your team scored a touchdown or something.

''Turns out that's the signal for 'ALL O.K. DO NOT WAIT!' Man, I can't believe it!'' Snow came and the lake froze over. He saw his first wolf, ''like a giant husky,'' tried to shoot it with his .22 and heard it yelp. But it crashed away into the underbrush. ''Bad shot and bad show of patience,'' he wrote.

By October, he was competing with wolves and foxes for the rabbits he snared. From the diary: ''It's been a terrible day for me and I won't go into it. Hands getting more frostbitten every day. Have only one meal of beans left. Honestly, I'm scared for my life. But I won't give up.''

In November, Mr. McCunn ran out of food. He considered trying to reach Fort Yukon on foot, 75 miles away. He wrote a letter to his father, telling him how to develop his film. He caught a squirrel, ''but that's only a tease even when you chew up and swallow all the bones too.''

Around Thanksgiving, he began having dizzy spells. ''I feel miserable,'' he wrote. ''Have had the chills upon awakening for the past three days. I can't take much more of this. Can't stop thinking about using the bullet.''

He used the last of his fuel, fed the fire a final time and wrote: ''Dear God in Heaven, please forgive me my weakness and my sins. Please look over my family.'' He added a separate note asking that his personal items be returned to his father, and he said that the person who found him should keep his rifle and shotgun. He signed his name and attached his Alaska driver's license. ''The I.D. is me, natch,'' he said in the diary's last entry.

Comment