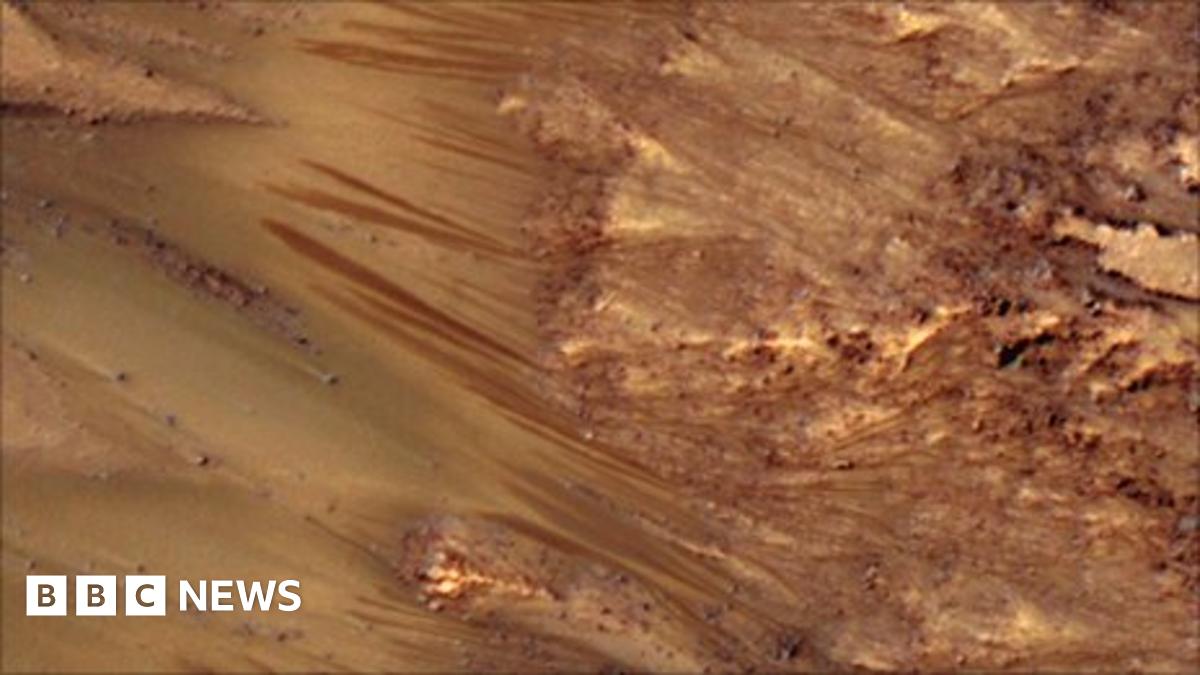

Striking new images from the mountains of Mars may be the best evidence yet of flowing, liquid water, an essential ingredient for life.

The findings, reported today in the journal Science, come from a joint US-Swiss study.

A sequence of images from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show many long, dark "tendrils" a few metres wide.

They emerge between rocky outcrops and flow hundreds of metres down steep slopes towards the plains below.

They appear on hillsides warmed by the summer sun, flow around obstacles and sometimes split or merge, but when winter returns, the tendrils fade away.

This suggests that they are made of thawing mud, say the researchers.

"It's hard to imagine they are formed by anything other than fluid seeping down slopes," said Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Project Scientist Richard Zurek of Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, but they appear when it's still too cold for fresh water.

Salty water

"The best explanation we have for these observations so far is flow of briny water, although this study does not prove that," said planetary geologist and lead author Professor Alfred McEwen of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona.

Saltiness lowers the temperature at which water freezes, and water about as salty as Earth's oceans could exist at these sites in summer.

"This could be the first flowing water," said Professor McEwen. This has profound implications in the search for extraterrestrial life.

"Liquid water is absolutely essential for life, and we've found life on Earth in pretty much every moist niche," said Dr Lewis Dartnell, astrobiologist at University College London, who was not involved in the study.

"So perhaps there could be hardy microbes surviving in these short periods of summer meltwater on the desert surface of Mars."

This was echoed by an expert on life in extreme environments, Professor Shiladitya DasSarma of the University of Maryland, also not involved in this study: "Their results are consistent with the presence of large and extensive underground salty lakes on Mars."

"This is an exciting possibility for those of us studying salt-loving (halophilic) micro-organisms here on Earth, since it opens the possibility that these kinds of hearty bugs may also inhabit our neighbouring planet," he said.

"Halophilic microbes are champions at withstanding the most punishing conditions, complete desiccation and ionising (space) radiation."

For geologist Joe Levy of Portland State University, a specialist in Antarctic desert ecosystems, who did not contribute to this work, they represent "a truly tantalising astrobiological target".

These small and mysterious tendrils could then be the best place to look for Martian life. Professor McEwen says that "for present-day life, these are the most accessible sites".

Comment