Chrissie Wellington's story:

Chrissie Wellington interview: The Iron Lady

Chrissie Wellington did not even discover sport until her early twenties. Now, the civil servant from rural Norfolk is the greatest female endurance athlete on the planet. Here, she describes the sacrifices she has made for ironman triathlon and why they are all worthwhile.

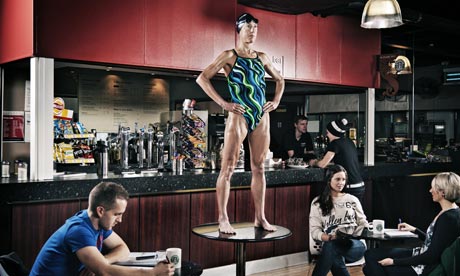

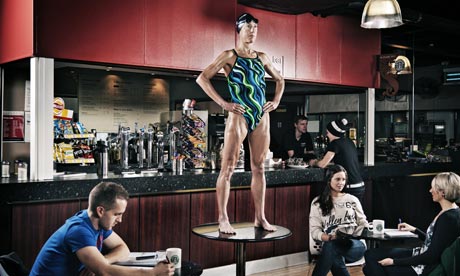

"This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined": ironman champion Chrissie Wellington at Birmingham University, her alma mater. Photograph: Shamil Tanna for the Observer

Chrissie Wellington interview: The iron ladyChrissie Wellington did not even discover sport until her early twenties. Now, the civil servant from rural Norfolk is the greatest female endurance athlete on the planet. Here, she describes the sacrifices she has made for ironman triathlon and why they are all worthwhile

Share Lena Corner

The Observer, Sunday 2 January 2011 Article history

"This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined": ironman champion Chrissie Wellington at Birmingham University, her alma mater. Photograph: Shamil Tanna for the Observer

It is rare to hear someone so openly appreciative of their own physique as Chrissie Wellington. "I love my body," she declares. "I am more than content with it. I take a holistic view and see it not just as the contours of my skin but as the muscles, sinews, bones and everything else. This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined. I do love it, and I don't mean that in an arrogant way."

Most 33-year old-women would rather curl up and die than pose, oiled up, in a swimsuit in the middle of a busy café. Not Wellington. She leaps on to a table in the canteen at Birmingham University in front of the gathered students and happily strikes pose after pose for the photographer. You can see why she shows such willing – hers is a body that has been worked on and honed to within an inch of its life. "I'm not flawless," she says standing, muscular arms akimbo, on the wobbly table. "I have unattractive feet, unruly hair and oversized calves, but I push this body to its absolute limit and it has never let me down."

Wellington is an ironman. That is, her chosen sport is a race which consists of a 3.8km swim, followed by a 180km bike ride, rounded off with a full marathon. It's one of the most hardcore tests of human endurance there is and comes with associated stories of medical horrors and bleeding athletes crawling over the finish line. She caused a sensation in the sport in 2007 when, in only her first year as a professional athlete, she won the ironman World Championship in Hawaii at her first attempt. Finishing five minutes ahead of the field, she blew her rivals out of the water and left commentators speechless because they had no idea who she was. She has continued to astound – rarely losing, outperforming even top male athletes and pushing her body to feats no one thought possible. She holds all the world records for her sport, wins many of her races by half an hour and is by some distance the greatest female endurance competitor in the world.

Wellington's story is even more remarkable because for a long time she had no inkling of these superhuman capabilities. Up until a few years ago she was an ordinary woman with an ordinary job in the civil service. As a child growing up in rural Norfolk right through to her early 20s, she never showed any sign of excelling athletically. "I never did any sport at a high level," she says. "Winning that race in Hawaii was surreal – I still have to pinch myself. I went from being a nobody to winning the biggest race in our sport on the biggest world stage. It changed my life forever."

It all started in 2001 when, not long out of Birmingham University with a degree in geography, Wellington decided to have a go at running the London Marathon. "I had just got back from travelling and had gained a bit of weight, so I started running as a way of controlling it," she says. "I wasn't fast and I didn't do it in a structured way – I just put on my old running shoes and went out and ran." Wellington got round in a little over three hours. "I never expected to do it that quickly," she says. "And I was surprised at how little discomfort I felt."

The following year she was gearing up to have another go when, cycling to work through Clapham, she was hit by a car. "I went over, smashed my chin, damaged my quad muscles and wasn't able to run for four months," she says. So Wellington started swimming instead and soon after was spotted in a pool by a coach who asked her if she'd ever considered a triathlon. "I'd never given it a moment's thought," she says, "but a seed was planted. I started thinking that I should give this triathlon malarkey a shot. I love the outdoors and I do love a challenge."

Wellington signed up to do a short super sprint triathlon and invited her parents to cheer her on. "They came up all the way from Norfolk to Redditch," she says. "It was pouring with rain. I was wearing a borrowed wetsuit and when I got into the water it flooded. I couldn't lift my arms and I almost sank. I had to be rescued by a kayaker. Not a very auspicious start."

Undeterred, Wellington signed up for a couple of longer races, both of which she won. "I was still very much a novice," she says. "The night before one of the races I had to be shown how to clip and unclip my shoes from my bike. But what I lacked in understanding of the sport I made up for in drive and determination."

After these wins she decided it was time to get herself a coach and joined a team headed by the controversial trainer Brett Sutton. Widely recognised as one of the best triathlon coaches in the sport, Sutton is also a convicted sex offender. In 1999 he admitted to five offences against a teenage swimmer in Australia and is banned from coaching there for life.

"There is a lot of controversy surrounding Brett, but he was absolutely fantastic for me," says Wellington. "He has an authoritarian coaching style which I found difficult, because I like to question things. It was also very hard for me to trust him, and initially our relationship was volatile. It was only when I gave myself over to him and stopped thinking and followed his every order without question that I started achieving success."

It was Sutton who spotted that Wellington had astonishing aerobic capabilities and mental strength, which made her perfect for competing over enormous distances. One of the first things he did was sign her up to do a long-course triathlon in Alpe d'Huez, which takes place on some of the gruelling climbs of the Tour de France. She got a puncture, catapulted over a crash barrier and still managed to win.

Five weeks after the Alps, Sutton sent Wellington to Korea to take part in her first ironman. "It was 90F, with 90% humidity, but even so I was chomping at the bit – I couldn't wait to race," she says. "My naivety in my capability was a blessing. I had no expectations. It turned out to be a war of attrition and a fight for survival because it was so incredibly, incredibly difficult. But I loved it, really loved it." She beat her nearest female rival by 50 minutes.

Which is how in October 2007, Wellington, equipped only for the first time with a proper time-trial bike, found herself on the starting line for the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii. She began with a distinctly average swim, three minutes slower than she was aiming for. Then at around 130km into the bike ride, with Sutton's words "Don't defer to anybody" ringing in her ears, she started moving up the pack. "I came up to the lead group of girls and instead of thinking: 'These are the champions and the best in the world', I just went straight past them." Even so, Wellington never believed she would hold on. "Halfway through the marathon I still never thought I would win," she says. "You know they are behind you and you never know what they are capable of. I was running scared the whole way, thinking: 'They'll catch me, they'll catch me.' But they just didn't."

As Wellington ran she used a number of mental tricks to propel her towards the finishing line. In her head she went over and over the lyrics from "Circle of Life" from the Lion King, Leona Lewis's "A Moment Like This" and Queen's "We are the Champions". "Quite embarrassing, really," she says. "Shows my total lack of taste in music." She also recited stanzas from Rudyard Kipling's "If" – a poem which was given to her by Sutton, the dog-eared photocopy of which she still takes to every race. "Because when you're 30k into the marathon," she says, "it's not your body that's carrying you, it's your mind."

There were no friends or family there to share Wellington's big moment. A few competitors she knew from the circuit supported her as she was thrust blinking into the limelight, but aside from that she was alone. It is still widely acknowledged as the biggest shock result ever seen in the sport, and she says that from the moment she crossed the finishing line to the end of that year everything passed in a blur.

Chrissie Wellington did not even discover sport until her early twenties. Now, the civil servant from rural Norfolk is the greatest female endurance athlete on the planet. Here, she describes the sacrifices she has made for ironman triathlon and why they are all worthwhile.

"This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined": ironman champion Chrissie Wellington at Birmingham University, her alma mater. Photograph: Shamil Tanna for the Observer

Chrissie Wellington interview: The iron ladyChrissie Wellington did not even discover sport until her early twenties. Now, the civil servant from rural Norfolk is the greatest female endurance athlete on the planet. Here, she describes the sacrifices she has made for ironman triathlon and why they are all worthwhile

Share Lena Corner

The Observer, Sunday 2 January 2011 Article history

"This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined": ironman champion Chrissie Wellington at Birmingham University, her alma mater. Photograph: Shamil Tanna for the Observer

It is rare to hear someone so openly appreciative of their own physique as Chrissie Wellington. "I love my body," she declares. "I am more than content with it. I take a holistic view and see it not just as the contours of my skin but as the muscles, sinews, bones and everything else. This body has taken me to heights that I never imagined. I do love it, and I don't mean that in an arrogant way."

Most 33-year old-women would rather curl up and die than pose, oiled up, in a swimsuit in the middle of a busy café. Not Wellington. She leaps on to a table in the canteen at Birmingham University in front of the gathered students and happily strikes pose after pose for the photographer. You can see why she shows such willing – hers is a body that has been worked on and honed to within an inch of its life. "I'm not flawless," she says standing, muscular arms akimbo, on the wobbly table. "I have unattractive feet, unruly hair and oversized calves, but I push this body to its absolute limit and it has never let me down."

Wellington is an ironman. That is, her chosen sport is a race which consists of a 3.8km swim, followed by a 180km bike ride, rounded off with a full marathon. It's one of the most hardcore tests of human endurance there is and comes with associated stories of medical horrors and bleeding athletes crawling over the finish line. She caused a sensation in the sport in 2007 when, in only her first year as a professional athlete, she won the ironman World Championship in Hawaii at her first attempt. Finishing five minutes ahead of the field, she blew her rivals out of the water and left commentators speechless because they had no idea who she was. She has continued to astound – rarely losing, outperforming even top male athletes and pushing her body to feats no one thought possible. She holds all the world records for her sport, wins many of her races by half an hour and is by some distance the greatest female endurance competitor in the world.

Wellington's story is even more remarkable because for a long time she had no inkling of these superhuman capabilities. Up until a few years ago she was an ordinary woman with an ordinary job in the civil service. As a child growing up in rural Norfolk right through to her early 20s, she never showed any sign of excelling athletically. "I never did any sport at a high level," she says. "Winning that race in Hawaii was surreal – I still have to pinch myself. I went from being a nobody to winning the biggest race in our sport on the biggest world stage. It changed my life forever."

It all started in 2001 when, not long out of Birmingham University with a degree in geography, Wellington decided to have a go at running the London Marathon. "I had just got back from travelling and had gained a bit of weight, so I started running as a way of controlling it," she says. "I wasn't fast and I didn't do it in a structured way – I just put on my old running shoes and went out and ran." Wellington got round in a little over three hours. "I never expected to do it that quickly," she says. "And I was surprised at how little discomfort I felt."

The following year she was gearing up to have another go when, cycling to work through Clapham, she was hit by a car. "I went over, smashed my chin, damaged my quad muscles and wasn't able to run for four months," she says. So Wellington started swimming instead and soon after was spotted in a pool by a coach who asked her if she'd ever considered a triathlon. "I'd never given it a moment's thought," she says, "but a seed was planted. I started thinking that I should give this triathlon malarkey a shot. I love the outdoors and I do love a challenge."

Wellington signed up to do a short super sprint triathlon and invited her parents to cheer her on. "They came up all the way from Norfolk to Redditch," she says. "It was pouring with rain. I was wearing a borrowed wetsuit and when I got into the water it flooded. I couldn't lift my arms and I almost sank. I had to be rescued by a kayaker. Not a very auspicious start."

Undeterred, Wellington signed up for a couple of longer races, both of which she won. "I was still very much a novice," she says. "The night before one of the races I had to be shown how to clip and unclip my shoes from my bike. But what I lacked in understanding of the sport I made up for in drive and determination."

After these wins she decided it was time to get herself a coach and joined a team headed by the controversial trainer Brett Sutton. Widely recognised as one of the best triathlon coaches in the sport, Sutton is also a convicted sex offender. In 1999 he admitted to five offences against a teenage swimmer in Australia and is banned from coaching there for life.

"There is a lot of controversy surrounding Brett, but he was absolutely fantastic for me," says Wellington. "He has an authoritarian coaching style which I found difficult, because I like to question things. It was also very hard for me to trust him, and initially our relationship was volatile. It was only when I gave myself over to him and stopped thinking and followed his every order without question that I started achieving success."

It was Sutton who spotted that Wellington had astonishing aerobic capabilities and mental strength, which made her perfect for competing over enormous distances. One of the first things he did was sign her up to do a long-course triathlon in Alpe d'Huez, which takes place on some of the gruelling climbs of the Tour de France. She got a puncture, catapulted over a crash barrier and still managed to win.

Five weeks after the Alps, Sutton sent Wellington to Korea to take part in her first ironman. "It was 90F, with 90% humidity, but even so I was chomping at the bit – I couldn't wait to race," she says. "My naivety in my capability was a blessing. I had no expectations. It turned out to be a war of attrition and a fight for survival because it was so incredibly, incredibly difficult. But I loved it, really loved it." She beat her nearest female rival by 50 minutes.

Which is how in October 2007, Wellington, equipped only for the first time with a proper time-trial bike, found herself on the starting line for the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii. She began with a distinctly average swim, three minutes slower than she was aiming for. Then at around 130km into the bike ride, with Sutton's words "Don't defer to anybody" ringing in her ears, she started moving up the pack. "I came up to the lead group of girls and instead of thinking: 'These are the champions and the best in the world', I just went straight past them." Even so, Wellington never believed she would hold on. "Halfway through the marathon I still never thought I would win," she says. "You know they are behind you and you never know what they are capable of. I was running scared the whole way, thinking: 'They'll catch me, they'll catch me.' But they just didn't."

As Wellington ran she used a number of mental tricks to propel her towards the finishing line. In her head she went over and over the lyrics from "Circle of Life" from the Lion King, Leona Lewis's "A Moment Like This" and Queen's "We are the Champions". "Quite embarrassing, really," she says. "Shows my total lack of taste in music." She also recited stanzas from Rudyard Kipling's "If" – a poem which was given to her by Sutton, the dog-eared photocopy of which she still takes to every race. "Because when you're 30k into the marathon," she says, "it's not your body that's carrying you, it's your mind."

There were no friends or family there to share Wellington's big moment. A few competitors she knew from the circuit supported her as she was thrust blinking into the limelight, but aside from that she was alone. It is still widely acknowledged as the biggest shock result ever seen in the sport, and she says that from the moment she crossed the finishing line to the end of that year everything passed in a blur.

Comment