Deep beneath desert sands, an embattled Middle Eastern state has built a covert nuclear bomb, using technology and materials provided by friendly powers or stolen by a clandestine network of agents. It is the stuff of pulp thrillers and the sort of narrative often used to characterise the worst fears about the Iranian nuclear programme. In reality, though, neither US nor British intelligence believe Tehran has decided to build a bomb, and Iran's atomic projects are under constant international monitoring.

The exotic tale of the bomb hidden in the desert is a true story, though. It's just one that applies to another country. In an extraordinary feat of subterfuge, Israel managed to assemble an entire underground nuclear arsenal – now estimated at 80 warheads, on a par with India and Pakistan – and even tested a bomb nearly half a century ago, with a minimum of international outcry or even much public awareness of what it was doing.

Despite the fact that the Israel's nuclear programme has been an open secret since a disgruntled technician, Mordechai Vanunu, blew the whistle on it in 1986, the official Israeli position is still never to confirm or deny its existence.

When the former speaker of the Knesset, Avraham Burg, broke the taboo last month, declaring Israeli possession of both nuclear and chemical weapons and describing the official non-disclosure policy as "outdated and childish" a rightwing group formally called for a police investigation for treason.

Meanwhile, western governments have played along with the policy of "opacity" by avoiding all mention of the issue. In 2009, when a veteran Washington reporter, Helen Thomas, asked Barack Obama in the first month of his presidency if he knew of any country in the Middle East with nuclear weapons, he dodged the trapdoor by saying only that he did not wish to "speculate".

UK governments have generally followed suit. Asked in the House of Lords in November about Israeli nuclear weapons, Baroness Warsi answered tangentially. "Israel has not declared a nuclear weapons programme. We have regular discussions with the government of Israel on a range of nuclear-related issues," the minister said. "The government of Israel is in no doubt as to our views. We encourage Israel to become a state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty [NPT]."

But through the cracks in this stone wall, more and more details continue to emerge of how Israel built its nuclear weapons from smuggled parts and pilfered technology.

The tale serves as a historical counterpoint to today's drawn-out struggle over Iran's nuclear ambitions. The parallels are not exact – Israel, unlike Iran, never signed up to the 1968 NPT so could not violate it. But it almost certainly broke a treaty banning nuclear tests, as well as countless national and international laws restricting the traffic in nuclear materials and technology.

The list of nations that secretly sold Israel the material and expertise to make nuclear warheads, or who turned a blind eye to its theft, include today's staunchest campaigners against proliferation: the US, France, Germany, Britain and even Norway.

Meanwhile, Israeli agents charged with buying fissile material and state-of-the-art technology found their way into some of the most sensitive industrial establishments in the world. This daring and remarkably successful spy ring, known as Lakam, the Hebrew acronym for the innocuous-sounding Science Liaison Bureau, included such colourful figures as Arnon Milchan, a billionaire Hollywood producer behind such hits as Pretty Woman, LA Confidential and 12 Years a Slave, who finally admitted his role last month.

"Do you know what it's like to be a twentysomething-year-old kid [and] his country lets him be James Bond? Wow! The action! That was exciting," he said in an Israeli documentary.

Milchan's life story is colourful, and unlikely enough to be the subject of one of the blockbusters he bankrolls. In the documentary, Robert de Niro recalls discussing Milchan's role in the illicit purchase of nuclear-warhead triggers. "At some point I was asking something about that, being friends, but not in an accusatory way. I just wanted to know," De Niro says. "And he said: yeah I did that. Israel's my country."

Milchan was not shy about using Hollywood connections to help his shadowy second career. At one point, he admits in the documentary, he used the lure of a visit to actor Richard Dreyfuss's home to get a top US nuclear scientist, Arthur Biehl, to join the board of one of his companies.

According to Milchan's biography, by Israeli journalists Meir Doron and Joseph Gelman, he was recruited in 1965 by Israel's current president, Shimon Peres, who he met in a Tel Aviv nightclub (called Mandy's, named after the hostess and owner's wife Mandy Rice-Davies, freshly notorious for her role in the Profumo sex scandal). Milchan, who then ran the family fertiliser company, never looked back, playing a central role in Israel's clandestine acquisition programme.

He was responsible for securing vital uranium-enrichment technology, photographing centrifuge blueprints that a German executive had been bribed into temporarily "mislaying" in his kitchen. The same blueprints, belonging to the European uranium enrichment consortium, Urenco, were stolen a second time by a Pakistani employee, Abdul Qadeer Khan, who used them to found his country's enrichment programme and to set up a global nuclear smuggling business, selling the design to Libya, North Korea and Iran.

For that reason, Israel's centrifuges are near-identical to Iran's, a convergence that allowed Israeli to try out a computer worm, codenamed Stuxnet, on its own centrifuges before unleashing it on Iran in 2010.

Arguably, Lakam's exploits were even more daring than Khan's. In 1968, it organised the disappearance of an entire freighter full of uranium ore in the middle of the Mediterranean. In what became known as the Plumbat affair, the Israelis used a web of front companies to buy a consignment of uranium oxide, known as yellowcake, in Antwerp. The yellowcake was concealed in drums labelled "plumbat", a lead derivative, and loaded onto a freighter leased by a phony Liberian company. The sale was camouflaged as a transaction between German and Italian companies with help from German officials, reportedly in return for an Israeli offer to help the Germans with centrifuge technology.

When the ship, the Scheersberg A, docked in Rotterdam, the entire crew was dismissed on the pretext that the vessel had been sold and an Israeli crew took their place. The ship sailed into the Mediterranean where, under Israeli naval guard, the cargo was transferred to another vessel.

US and British documents declassified last year also revealed a previously unknown Israeli purchase of about 100 tons of yellowcake from Argentina in 1963 or 1964, without the safeguards typically used in nuclear transactions to prevent the material being used in weapons.

Israel had few qualms about proliferating nuclear weapons knowhow and materials, giving South Africa's apartheid regime help in developing its own bomb in the 1970s in return for 600 tons of yellowcake.

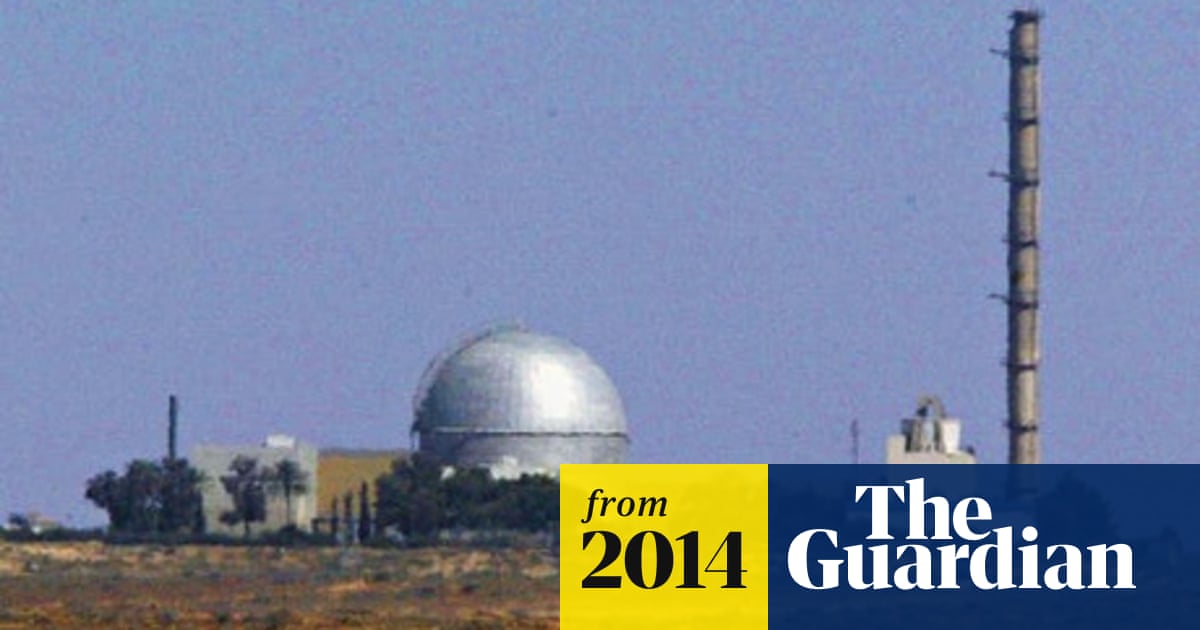

Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been camouflaged. Photograph: space imaging

Israel's nuclear reactor also required deuterium oxide, also known as heavy water, to moderate the fissile reaction. For that, Israel turned to Norway and Britain. In 1959, Israel managed to buy 20 tons of heavy water that Norway had sold to the UK but was surplus to requirements for the British nuclear programme. Both governments were suspicious that the material would be used to make weapons, but decided to look the other way. In documents seen by the BBC in 2005 British officials argued it would be "over-zealous" to impose safeguards. For its part, Norway carried out only one inspection visit, in 1961.

Israel's nuclear-weapons project could never have got off the ground, though, without an enormous contribution from France. The country that took the toughest line on counter-proliferation when it came to Iran helped lay the foundations of Israel's nuclear weapons programme, driven by by a sense of guilt over letting Israel down in the 1956 Suez conflict, sympathy from French-Jewish scientists, intelligence-sharing over Algeria and a drive to sell French expertise and abroad.

"There was a tendency to try to export and there was a general feeling of support for Israel," Andre Finkelstein, a former deputy commissioner at France's Atomic Energy Commissariat and deputy director general at the International Atomic Energy Agency, told Avner Cohen, an Israeli-American nuclear historian.

The exotic tale of the bomb hidden in the desert is a true story, though. It's just one that applies to another country. In an extraordinary feat of subterfuge, Israel managed to assemble an entire underground nuclear arsenal – now estimated at 80 warheads, on a par with India and Pakistan – and even tested a bomb nearly half a century ago, with a minimum of international outcry or even much public awareness of what it was doing.

Despite the fact that the Israel's nuclear programme has been an open secret since a disgruntled technician, Mordechai Vanunu, blew the whistle on it in 1986, the official Israeli position is still never to confirm or deny its existence.

When the former speaker of the Knesset, Avraham Burg, broke the taboo last month, declaring Israeli possession of both nuclear and chemical weapons and describing the official non-disclosure policy as "outdated and childish" a rightwing group formally called for a police investigation for treason.

Meanwhile, western governments have played along with the policy of "opacity" by avoiding all mention of the issue. In 2009, when a veteran Washington reporter, Helen Thomas, asked Barack Obama in the first month of his presidency if he knew of any country in the Middle East with nuclear weapons, he dodged the trapdoor by saying only that he did not wish to "speculate".

UK governments have generally followed suit. Asked in the House of Lords in November about Israeli nuclear weapons, Baroness Warsi answered tangentially. "Israel has not declared a nuclear weapons programme. We have regular discussions with the government of Israel on a range of nuclear-related issues," the minister said. "The government of Israel is in no doubt as to our views. We encourage Israel to become a state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty [NPT]."

But through the cracks in this stone wall, more and more details continue to emerge of how Israel built its nuclear weapons from smuggled parts and pilfered technology.

The tale serves as a historical counterpoint to today's drawn-out struggle over Iran's nuclear ambitions. The parallels are not exact – Israel, unlike Iran, never signed up to the 1968 NPT so could not violate it. But it almost certainly broke a treaty banning nuclear tests, as well as countless national and international laws restricting the traffic in nuclear materials and technology.

The list of nations that secretly sold Israel the material and expertise to make nuclear warheads, or who turned a blind eye to its theft, include today's staunchest campaigners against proliferation: the US, France, Germany, Britain and even Norway.

Meanwhile, Israeli agents charged with buying fissile material and state-of-the-art technology found their way into some of the most sensitive industrial establishments in the world. This daring and remarkably successful spy ring, known as Lakam, the Hebrew acronym for the innocuous-sounding Science Liaison Bureau, included such colourful figures as Arnon Milchan, a billionaire Hollywood producer behind such hits as Pretty Woman, LA Confidential and 12 Years a Slave, who finally admitted his role last month.

"Do you know what it's like to be a twentysomething-year-old kid [and] his country lets him be James Bond? Wow! The action! That was exciting," he said in an Israeli documentary.

Milchan's life story is colourful, and unlikely enough to be the subject of one of the blockbusters he bankrolls. In the documentary, Robert de Niro recalls discussing Milchan's role in the illicit purchase of nuclear-warhead triggers. "At some point I was asking something about that, being friends, but not in an accusatory way. I just wanted to know," De Niro says. "And he said: yeah I did that. Israel's my country."

Milchan was not shy about using Hollywood connections to help his shadowy second career. At one point, he admits in the documentary, he used the lure of a visit to actor Richard Dreyfuss's home to get a top US nuclear scientist, Arthur Biehl, to join the board of one of his companies.

According to Milchan's biography, by Israeli journalists Meir Doron and Joseph Gelman, he was recruited in 1965 by Israel's current president, Shimon Peres, who he met in a Tel Aviv nightclub (called Mandy's, named after the hostess and owner's wife Mandy Rice-Davies, freshly notorious for her role in the Profumo sex scandal). Milchan, who then ran the family fertiliser company, never looked back, playing a central role in Israel's clandestine acquisition programme.

He was responsible for securing vital uranium-enrichment technology, photographing centrifuge blueprints that a German executive had been bribed into temporarily "mislaying" in his kitchen. The same blueprints, belonging to the European uranium enrichment consortium, Urenco, were stolen a second time by a Pakistani employee, Abdul Qadeer Khan, who used them to found his country's enrichment programme and to set up a global nuclear smuggling business, selling the design to Libya, North Korea and Iran.

For that reason, Israel's centrifuges are near-identical to Iran's, a convergence that allowed Israeli to try out a computer worm, codenamed Stuxnet, on its own centrifuges before unleashing it on Iran in 2010.

Arguably, Lakam's exploits were even more daring than Khan's. In 1968, it organised the disappearance of an entire freighter full of uranium ore in the middle of the Mediterranean. In what became known as the Plumbat affair, the Israelis used a web of front companies to buy a consignment of uranium oxide, known as yellowcake, in Antwerp. The yellowcake was concealed in drums labelled "plumbat", a lead derivative, and loaded onto a freighter leased by a phony Liberian company. The sale was camouflaged as a transaction between German and Italian companies with help from German officials, reportedly in return for an Israeli offer to help the Germans with centrifuge technology.

When the ship, the Scheersberg A, docked in Rotterdam, the entire crew was dismissed on the pretext that the vessel had been sold and an Israeli crew took their place. The ship sailed into the Mediterranean where, under Israeli naval guard, the cargo was transferred to another vessel.

US and British documents declassified last year also revealed a previously unknown Israeli purchase of about 100 tons of yellowcake from Argentina in 1963 or 1964, without the safeguards typically used in nuclear transactions to prevent the material being used in weapons.

Israel had few qualms about proliferating nuclear weapons knowhow and materials, giving South Africa's apartheid regime help in developing its own bomb in the 1970s in return for 600 tons of yellowcake.

Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been Pictures of the secret Dimona nuclear reactor in Israel, showing where the plant has allegedly been camouflaged. Photograph: space imaging

Israel's nuclear reactor also required deuterium oxide, also known as heavy water, to moderate the fissile reaction. For that, Israel turned to Norway and Britain. In 1959, Israel managed to buy 20 tons of heavy water that Norway had sold to the UK but was surplus to requirements for the British nuclear programme. Both governments were suspicious that the material would be used to make weapons, but decided to look the other way. In documents seen by the BBC in 2005 British officials argued it would be "over-zealous" to impose safeguards. For its part, Norway carried out only one inspection visit, in 1961.

Israel's nuclear-weapons project could never have got off the ground, though, without an enormous contribution from France. The country that took the toughest line on counter-proliferation when it came to Iran helped lay the foundations of Israel's nuclear weapons programme, driven by by a sense of guilt over letting Israel down in the 1956 Suez conflict, sympathy from French-Jewish scientists, intelligence-sharing over Algeria and a drive to sell French expertise and abroad.

"There was a tendency to try to export and there was a general feeling of support for Israel," Andre Finkelstein, a former deputy commissioner at France's Atomic Energy Commissariat and deputy director general at the International Atomic Energy Agency, told Avner Cohen, an Israeli-American nuclear historian.

Comment